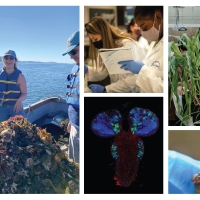

Biology student researchers investigate possible connection between fungal pathogen and frog mating

Student research at SFSU leads to a new article on frog calls and deadly infections in the journal Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology

What noise does a frog make? Many of us would say “ribbit, ribbit.” Funnily enough, the Pacific tree frog (aka Pacific chorus frog) is the only species that really ribbits. (Listen to the variety of “peep,” “waaaaaaa,” “pa-tank,” and more sounds from other species on AmphibiaWeb.) Given how widespread Pacific tree frogs are in California, there’s a chance you’ve seen or heard their ribbits yourself.

During mating season, female frogs in this species choose males based on variations in their call — something scientists find intriguing from an evolutionary standpoint. “If all females have the same preference for type of call, then why haven’t all males evolved to have the exact call and be uniform?” said Julia Messersmith (M.S., ’21). “One theory is the Hamilton-Zuk hypothesis.”

The hypothesis connects male frog calls to their possible resistance to parasitism, a serious global problem facing amphibians. Messersmith studied this hypothesis for her master’s thesis at San Francisco State University and published her findings in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. She and two other SFSU students co-authored the paper with their faculty advisers, SFSU Biology Professor and Department Chair Vance Vredenburg and Associate Professor Alejandro Vélez (now at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville).

The 40-year-old Hamilton-Zuk hypothesis posits that male frogs’ mating call traits (or plumage traits in birds) are related to their health, specifically their resistance to parasitism. Like other amphibians, Pacific tree frogs are in danger of contracting Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), a fungal pathogen killing amphibians worldwide. If the Hamilton-Zuk hypothesis is right, it’s possible that female frogs are preferentially choosing the calls of “healthier” males. Although Bd infection is normally lethal, Pacific tree frogs sometimes fare better than other species — but this makes them effective carriers for disease who can spread the pathogen to other amphibians via water or direct contact.